In his article on The Intercept, unjustly imprisoned US journalist and activist Barrett Brown relates his experience of joining Lakota Indians inmates friends for a Temazcal / sweat lodge ceremony, from building the bonfire to sweating and singing together inside the hut. Temazcal are powerful collective physical and spiritual healing ceremonies practised by native Americans, with strong emphasis on the natural elements, fire, water, air, earth.

Recommended: More Barrett Brown Prison Writing

Donate, Write, Send a book : HELP Barrett Brown HERE

” In the meantime, I continue to have neat adventures. Last month one of the American Indian inmates invited me to attend their weekly sweat lodge ceremony, which is held in a fenced-off area that each federal prison is required to provide for ritual use by the Natives. The next morning I showed up at the appointed time and, having determined that it wasn’t an ambush, I began helping the 20 or so resident Indians break up tree branches for fire kindling, something I did very much with the air of a five-year-old who believes himself to be “helping Daddy.” Next we built a large bonfire (I assisted by staying out the way and being good) by which to heat up several dozen large rocks that would be used for “the sweat.” The fire-making process was expedited by strategically placed crumpled-up sheets of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, which I gather is not a strictly traditional aspect of most shamanistic ceremonies. As if to acknowledge this, one of the Indians declared, “The one good thing the white man ever did was invent paper.” Naturally all eyes were on me, and I knew that this might be my only chance to win them over. “We didn’t invent it,” I blurted out. “We just stole it from the Chinese.” This produced appreciative chuckles all around. “I got a laugh out of the Indians!” I thought exultantly, my triumph so complete that I was unbothered by the fact that what I’d said wasn’t really true.

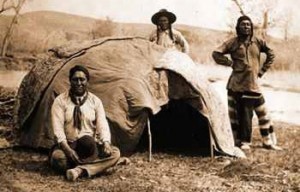

By and by we crawled into the lodge, a wood-and-canvas structure with a dirt floor, in the middle of which had been dug a pit to hold the heated rocks that would be providing the extraordinary heat we would need to sweat out our sins. The flap was then closed from the outside, leaving us in perfect darkness, and thereafter began the first of the 15-minute “rounds” of the sweat ceremony, which consisted of all manner of tribal songs, entreaties to the spirits, and sometimes just discussions and announcements. At one point my sponsor, a Lakota, declared that although superficially white, I might nonetheless have an “Indian spirit.” It was one of the nicest things anyone had ever said about me, this polite supposition that I might not really be descended from the fair-skinned race of marauding, treaty-breaking slavers whose Novus Ordo Seclorum had been built on a foundation of genocide. But insomuch as I’d spent the bulk of the ceremony not in prayer, but rather in a state of neurotic concern over whether or not my self-deprecating comment from an hour earlier about whites stealing paper could have perhaps been a bit more crisply phrased, I’m afraid my spirit would seem to be Anglo-Saxon after all.

Although undeniably majestic, the ceremony was also something of a disappointment. I had gone into the thing hoping that I might mysteriously know exactly what to do — how to pass the peace pipe and all that — and maybe even start singing old Cherokee songs that the eldest of those present would barely recall having heard from their own grandfathers. Stunned, the Indians would collectively intone, “He shall know your ways as if born to them,” this being the ancient prophecy I had thereby fulfilled, and then I would unite the tribes under my banner and lead the foremost of their warriors on a jihad against our shared enemies, as Paul Muad’Dib did. Instead, the Indians had to remind me several times not to just stand up and start walking around during the ceremony.”